Thousands of US health care workers go on strike in multiple states over wages and staff shortages

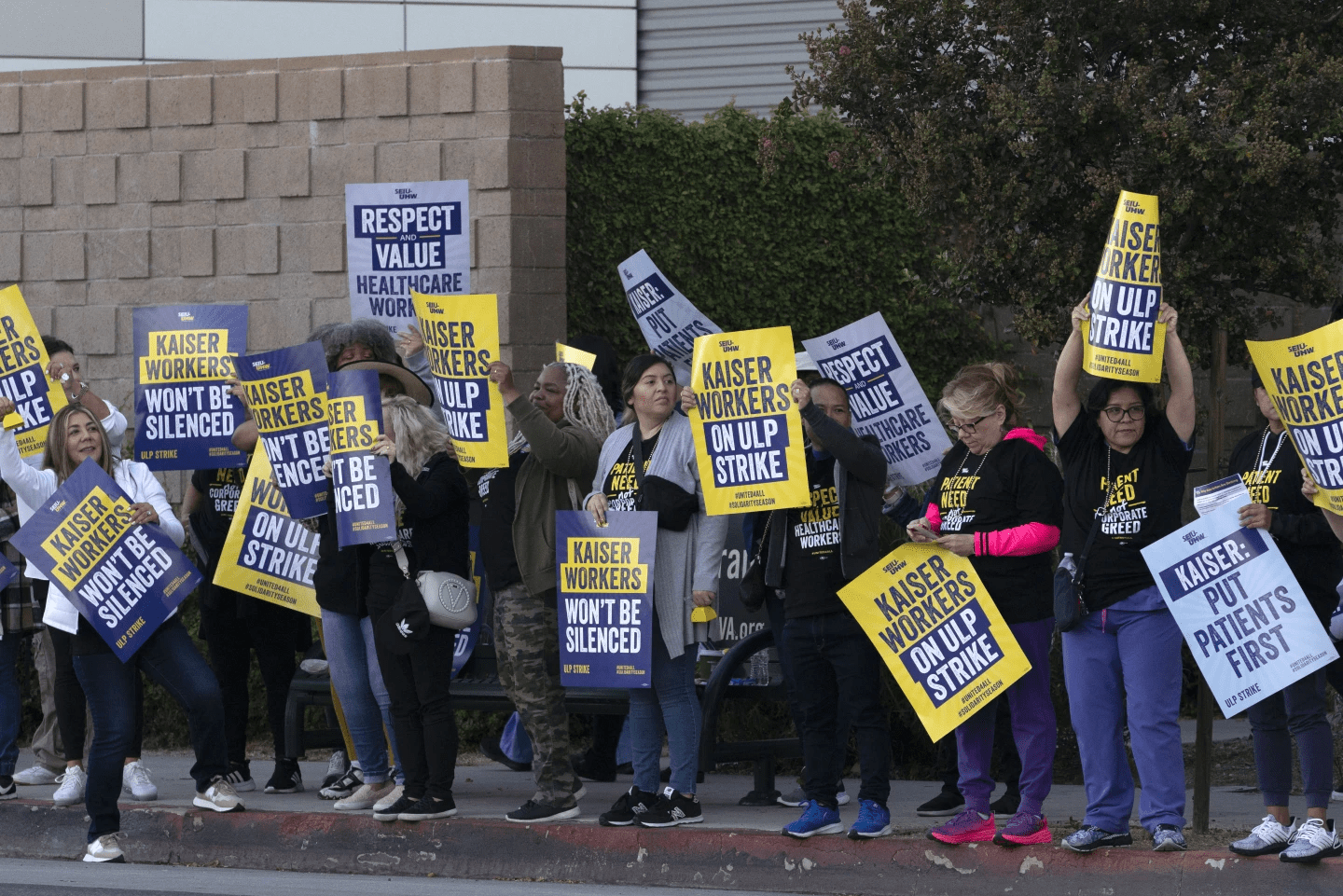

Kaiser Permanente workers carry protest signs outside the hospital during a strike in the Panorama City section of Los Angeles on Wednesday, Oct. 4, 2023. Picketing has begun at Kaiser Permanente hospitals as some 75,000 workers who say understaffing is hurting patient care go on strike in five states and the District of Columbia. It marks the latest major labor unrest in the U.S. Kaiser Permanente is one of the country's larger insurers and health care system operators. (Credit: AP/Richard Vogel)

LOS ANGELES (AP) — Some 75,000 Kaiser Permanente workers walked off the job Wednesday in multiple states, kicking off a major health care strike in an extraordinary year for U.S. labor organizing and work stoppages.

Kaiser Permanente is one of the country’s larger insurers and health care system operators, serving nearly 13 million people. The nonprofit company, based in Oakland, California, said its 39 hospitals, including emergency rooms, will remain open during the picketing, though appointments and non-urgent procedures could be delayed.

The Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, representing about 85,000 of the health system’s employees nationally, approved a strike for three days in California, Colorado, Oregon and Washington, and for one day in Virginia and Washington, D.C.

“They’re not listening to the frontline health care workers,” said Mikki Fletchall, a licensed vocational nurse based in a Kaiser medical office in Camarillo, California. “We’re striking because of our patients.”

Early Wednesday, workers at Kaiser Permanente Los Angeles Medical Center cheered as the strike deadline arrived. The strikers include licensed vocational nurses, home health aides and ultrasound sonographers, as well as technicians in the radiology, X-ray, surgical, pharmacy and emergency departments.

Brittany Everidge, a ward clerk transcriber in the medical center’s maternal child health department, was among those on the picket line. She said because of staffing shortages, pregnant people in active labor can be stuck waiting for hours to be checked in. Other times, too few transcribers can lead to delays in creating and updating charts for new babies.

“We don’t ever want to be in a situation where the nurses have to do our job,” she said.

Doctors are not participating in the strike, and Kaiser said it was bringing in thousands of temporary workers.

The strike comes in a year when there have been work stoppages within multiple industries, including, transportation, entertainment and hospitality.

The health care industry alone has been hit by several strikes this year as it confronts burnout from heavy workloads — problems that were exacerbated greatly by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Unions representing Kaiser workers in August asked for a $25 hourly minimum wage, as well as increases of 7% each year in the first two years and 6.25% each year in the two years afterward.

Union members say understaffing is boosting the hospital system’s profits but hurting patients, and executives have been bargaining in bad faith during negotiations.

Tonya Harris, who was on the picket line in Irvine, about 40 miles (64 kilometers) south of Los Angeles in Orange County, said medical assistants like her are often asked to double up with doctors – each of whom has up to 20 patients – instead of working one-to-one.

“You’re running around and you’re trying to basically keep up with the flow,” she said, wearing her strike captain vest over her scrubs.

The single mother with two kids going into college said she also can’t afford to live in Orange County on her current pay.

Kaiser has proposed minimum hourly wages of between $21 and $23 next year depending on the location.

Since 2022, the hospital system has hired 51,000 workers and has plans to add 10,000 more people by the end of the month.

Kaiser Permanente reported $2.1 billion in net income for this year’s second quarter on more than $25 billion in operating revenue. But the company said it still was dealing with cost headwinds and challenges from inflation and labor shortages.

Kaiser executive Michelle Gaskill-Hames defended the company and said its practices, compensation and retention are better than its competitors, even as the entire sector faces the same challenges.

“Our focus, for the dollars that we bring in, are to keep them invested in value-based care,” said Gaskill-Hames, president of Kaiser Foundation Health Plan and Hospitals of Southern California and Hawaii.

She added that Kaiser only faces 7% turnover compared to the industry standard of 21%, despite the effects of the pandemic.

“I think coming out of the pandemic, health care workers have been completely burned out,” she said. “The trauma that was felt caring for so many COVID patients, and patients that died, was just difficult.”

The workers’ last contract was negotiated in 2019, before the pandemic.

Hospitals generally have struggled in recent years with high labor costs, staffing shortages and rising levels of uncompensated care, according to Rick Gundling, a senior vice president with the Healthcare Financial Management Association, a nonprofit that works with health care finance executives.

Most of their revenue is fixed, coming from government-funded programs like Medicare and Medicaid, Gundling noted. He said that means revenue growth is “only possible by increasing volumes, which is difficult even under the best of circumstances.”

Meanwhile, workers calling for higher wages, better working conditions and job security, especially since the end of the pandemic, have been increasingly willing to walk out on the job as employers face a greater need for workers.

The California legislature has sent Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom a bill that would increase the minimum wage for the state’s 455,000 health care workers to $25 per hour over the next decade. The governor has until Oct. 14 to decide whether to sign or veto it.

___

Associated Press Writer Tom Murphy in Indianapolis contributed to this report.